From advance to retreat: The 2024 SA Elections

Women, Gender And Youth Inclusion In South Africa’s Second Government Of National Unity

South Africa’s 2024 national and provincial elections saw the African National Congress (ANC) obtain 40% of the vote, and lose its once unassailable majority. No party won a sufficient majority to be able to form a government. This necessitated the formation of a coalition government. President Cyril Ramaphosa announced the 2024 National and Provincial Election result as a “victory for democracy.” He noted that the election results indicate “that the people of South Africa expect their leaders to work together to meet their needs”

This refrain served as justification for the establishment of a coalition comprising 11 political parties, dubbed the second Government of National Unity (GNU) in South Africa (the first in 1994). The first GNU was regulated by the then interim Constitution and prescribed that all parties with support above a threshold of 10% would be entitled to a seat in the Executive and that the public service and existing public servants would retain their posts for a period of at least five years and be granted their perks. The current GNU is a voluntary agreement, though underpinned by a written coalition agreement.

Proponents of the second GNU assert that it is based on the “will of the people,” and that the election results should be interpreted as a directive from the electorate for a more inclusive, cooperative governance mode. Voters, however, are not homogenous: they differed by age, race, gender, geography, religion, ideology, party affinity and other demographics. Presumably, therefore, they would also differ in what they consider as priorities for South Africa after 30 years of democratic governance, and naturally would differ as to who their preferred political party would be who they believe would best meet their needs and aspirations.

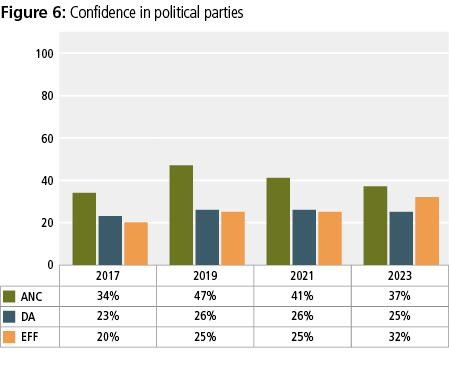

The spread and dispersal of votes by the electorate can also therefore, be interpreted as a lack of trust in political parties and political leaders, which obviously explains why no single party was able to gain an outright majority. This was made evident in the findings on the lack of trust in political parties. The Afrobarometer survey found that in South Africa 27 % of people surveyed had “somewhat” or a “lot of trust” in the then ruling party, while a whopping 71% said their trust the ruling party was either “not a lot”, or “not at all”. For opposition, Afrobarometer found that 24% of respondents had “somewhat” or a “lot of trust” in the opposition parties, and 72% “not a lot” or “not at all”. [1]

These findings are shored up by findings of the South African Reconciliation Barometer on people’s confidence in political parties[2]

The Inclusion of Women and young people.

Women constituted 55% (15 345033) of eligible voters.

Young voters, under the age of 40, constituted 42.4% (11 790 661) of the electorate.

It can reasonably be assumed that these voters would want to see their demographic equitably represented in the new dispensation that they, wittingly or unwittingly, ushered in through their vote.

However, of the 14 866 candidates on the IEC’s nominations list, only 42% (6234) were women, and 32% (4892) were under the age of 40. As per IEC data, there were 15 first-time voters (i.e. age 18) nominated to stand for elections. The nomination of party candidates was not equitable or proportionate to the diversity profile of the society and the electorate.

The ANC’s Statement of Intent of a GNU listed some foundational principles as the basis for joining the proposed post-election coalition. Among these were constitutionalism, non-racialism, non-sexism, and “peace stability and safe communities, especially for women and children.” The ANC’s original vision of political inclusion in the GNU, therefore, appeared to be broader than mere political party representation, it sought to reflect the diversity of the society as intended by the constitution. However, gender parity and equality appeared to be less of a priority for inclusion in the actual formation of the new government. Political expediency gained the upper hand in the considerations of the GNU formation. The GNU is currently composed of 11 diverse parties, which is very inclusive of political parties, but insufficiently inclusive of the diversity of people and the demographics of the society, generally. Some of the parties in the GNU have a questionable commitment and adherence to the principles of non-racism and non-sexism – something that South Africa’s Constitution explicitly commits the government to – especially on the principles of inclusivity and gender equality. In the composition of the new GNU, women’s representation in parliament declined from 46% in 2020 to 43% in 2024. In the Executive, of the current 77 ministers, there are 31 women, making up 40% of the executive. South Africa’s cabinet reached gender parity in 2019. This gain has been substantially reversed in the composition of new GNU. In general, South Africa went from being the country with the highest number of women in parliament in Southern Africa to now being in 3rd place. Worse, it has declined to 22nd place globally according to IDEA’s Women’s Political Participation in Africa Barometer 2024[3].

The ANC’s quota system (which it introduced during the 2009 elections) had significantly increased women’s representation in parliament in prior years. The ANC was one of the few parties that retained gender parity in its nominations and currently has 53% of its parliamentary representatives as women. The Economic Freedom Front (EFF) also surpassed the 50% mark with 54% of its current representatives in parliament, being women. However, with the ANC’s loss of aggregate electoral support, there has been a concomitant decline in the number of seats that the ANC won. This has resulted in a corresponding decline in women’s overall representation, especially since other political parties do not implement a 50% gender parity in their nominations processes. The Democratic Alliance (DA) currently has 32% women and the uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MKP) 35%, while the Inkatha Freedom Party has 29% of women in their parliamentary benches, respectively. This has impacted significantly on South Africa’s gender representation in the National Assembly.

In appointing the national executive, the President has significant prerogative and exclusive formal powers (notwithstanding the pressure to consult their parties and other political stakeholders). With these powers in mind, the president could exercise prerogative and therefore select and appoint the cabinet to ensure, or at least contribute to advancing, gender parity. It is evident that in appointing the Executive in this new GNU, for President Ramaphosa, political interests and other considerations predominated. Consequently, we have witnessed the largest drop in women’s representation post the 2024 national and provincial elections. This backsliding on gender equality was becoming evident, even in the lead up to the elections, with none of the top political parties highlighting gender related issues in their campaigns until, the very last week of the elections when this glaring gap and omission of a vital public policy and societal problem was highlighted by gender analysts. Simply put, gender was a non-issue for political parties during the elections, even though the majority among the electorate were women.

Factoring in the Youth

The youth, in contrast to women, received much more attention from political parties. Concomitantly, South Africa’s seventh administration now has many more, younger members of parliament and ministers. The youngest parliamentarian is 20 years old, the Patriotic Alliance’s Cleo Wilskut, whilst the average age of those appointed to cabinet has reduced from 61 to 54 years. The Democratic Alliance (DA) has four young ministers, Siviwe Gwarube (34); Leon Schreiber (35); Solly Malatsi (38) and Dean McPherson (39) in cabinet. Patricia DeLille is the eldest (at 73) followed by Cyril Ramaphosa (71), Gwede Mantashe (69), Angie Motshekga (69) and Pieter Groenewald (68).

Ironically, the DA, with the greatest number of young people represented in Cabinet, also has the one of the lowest representations of women in the National Assembly. It is also noticeable that the DA’s stronghold and largest constituency of support is in the Western Cape, where the majority demographic is “Coloured” (in the racial parlance in South Africa), and yet none of the DA’s representatives in the National Executive of the GNU are drawn from this community. While the DA asserts the principle of meritocratic governance, this begs the question of whether meritocracy is mutually exclusive of identity-based representation?

The Key Points

The 2024 elections have provided us with some important insights in relation to inclusion. First, thirty years into democracy, women’s political representation is still largely dependent on quotas.

Second, gender equality appears to be an expendable value and commitment when the political stakes are high, and is compromised in favour of other considerations,

Third, there seems to be a growing trend to trade off gender equality for youth inclusion of youth. As the representation of youth increases, gender representation declines, since women and youth seem to have to share the 50% in the parity provisions striving for equity and inclusion, while older men continue to hold onto 50% of power and privilege.

Finally, political parties appear to conveniently interpret the mandate of the electorate as that of “power sharing.” This sharing of power is premised on political party interests and comes at the expense and exclusion of the hard-won rights and influence of the constituencies (i.e. women in the main) who effectively voted parties into positions of authority.

Women, in the face of a back-sliding on gender equality, need to effectively [re]mobilise and be vigilant to maintain and advance their rights and interests. The challenges confronting South Africa impact men, women, youth and those with disabilities, and different racial groups, differentially. South Africa’s government should therefore meaningfully include representatives of its diverse society to ensure appropriate policy responses and the well- being of all, as summed up in the adage: “nothing about us, without us.”

[1] Mikahil Moosa, and Jan Hofmeyr. “South Africans’ trust in institutions and representatives reaches new low.” 2021. Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 474, Institute for Justice and Reconciliation and Afrobarometer. Figure 1 and figure 12: https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/migrated/files/publications/Dispatches/ad474-south_africans_trust_in_institutions_reaches_new_low-afrobarometer-20aug21.pdf

[2] Kate Lefko-Everett, “SA Reconciliation Barometer, 2023 Report”. Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

[3]International IDEA, “Women’s Political Participation: Africa Barometer 2024”, 2nd edition: https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/womens-political-participation-africa-barometer-2024

The South African Elections Weekly Briefs are produced through a partnership between the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa, Media Monitoring Africa and the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation. The purpose of the partnership intervention is to strengthen peaceful and inclusive participatory electoral processes in South Africa.