Trust in the Government and its institutions. What support for a GNU governing coalition in South Africa?

Despondency and the lack of trust

Leading in to the 2024 elections, the majority of South Africans felt – and were feeling for some time – that, on balance, the country was heading in the wrong direction – in the direction opposite to the democratic and inclusive society that the South African Constitution articulates as the goal of government.

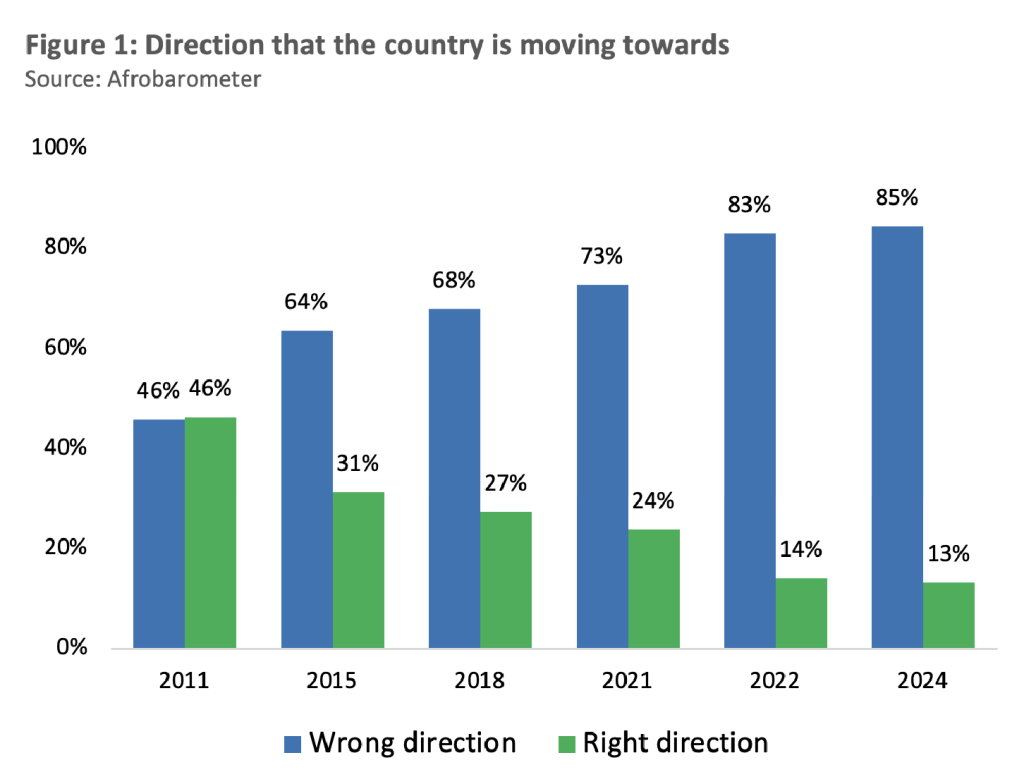

The Afrobarometer – an African continental public opinion survey that measures African sentiments on issues of governance in close to 40 countries across the African continent including South Africa – shows public sentiments of South Africans about the overall direction of the country over the past thirteen years. Its findings are unambiguous. South Africans have become overwhelmingly negative about the general direction that the country has been moving in. As the graphic in figure one details, in 2011 opinion was evenly split between those who were negative and those positive – at 46%, about the country’s trajectory. By 2024, positive sentiment had declined to a mere 13%, while negative sentiment almost doubled to 85%. Consequently, it is not implausible to argue that, over time, the majority of South Africans experienced a back slide in their life-experiences.

Question: Would you say that the country is going in the wrong direction or going in the right direction?

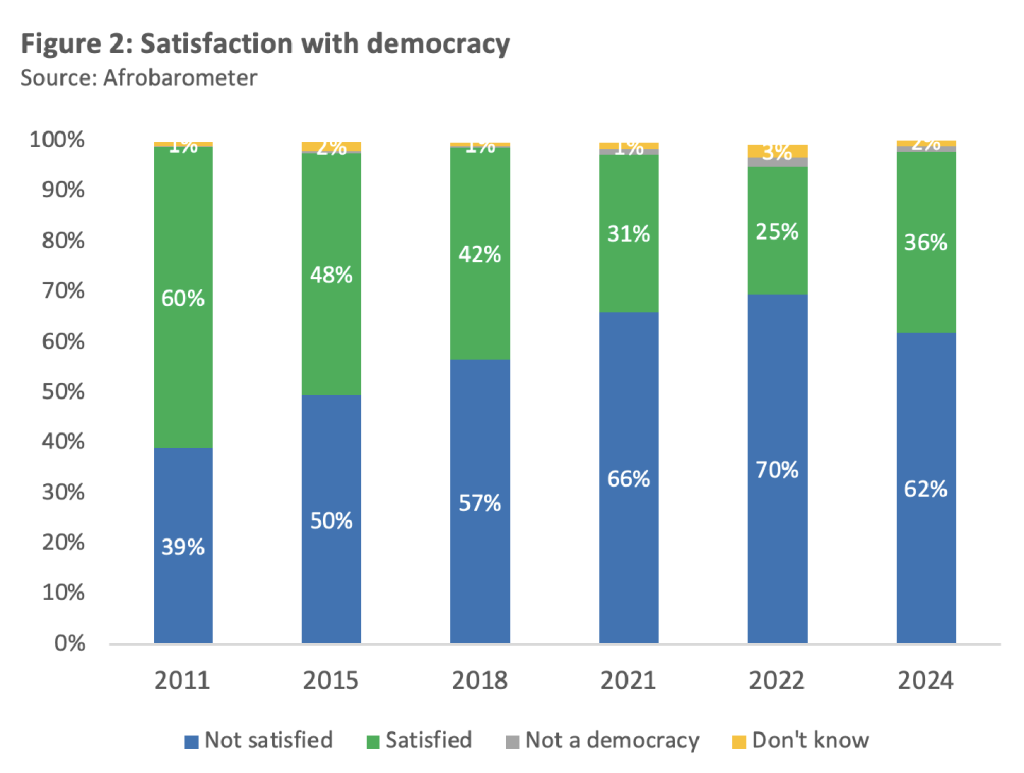

Between 2011 and 2024 levels of satisfaction with the functioning of the democratic state almost halved from 60% to 39% as demonstrated in the data from Afrobarometer presented in Figure 2. Dissatisfaction with democracy has almost doubled during the same period. Though the majority of South Africans still appeared to prefer democracy above other forms of government, these findings underscore the reality that the gap between expectation and experience of democracy and democratic government, is increasingly becoming wider.

Question: Overall, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in South Africa?

Dysfunctional Democracy & Government – driven by lack of trust.

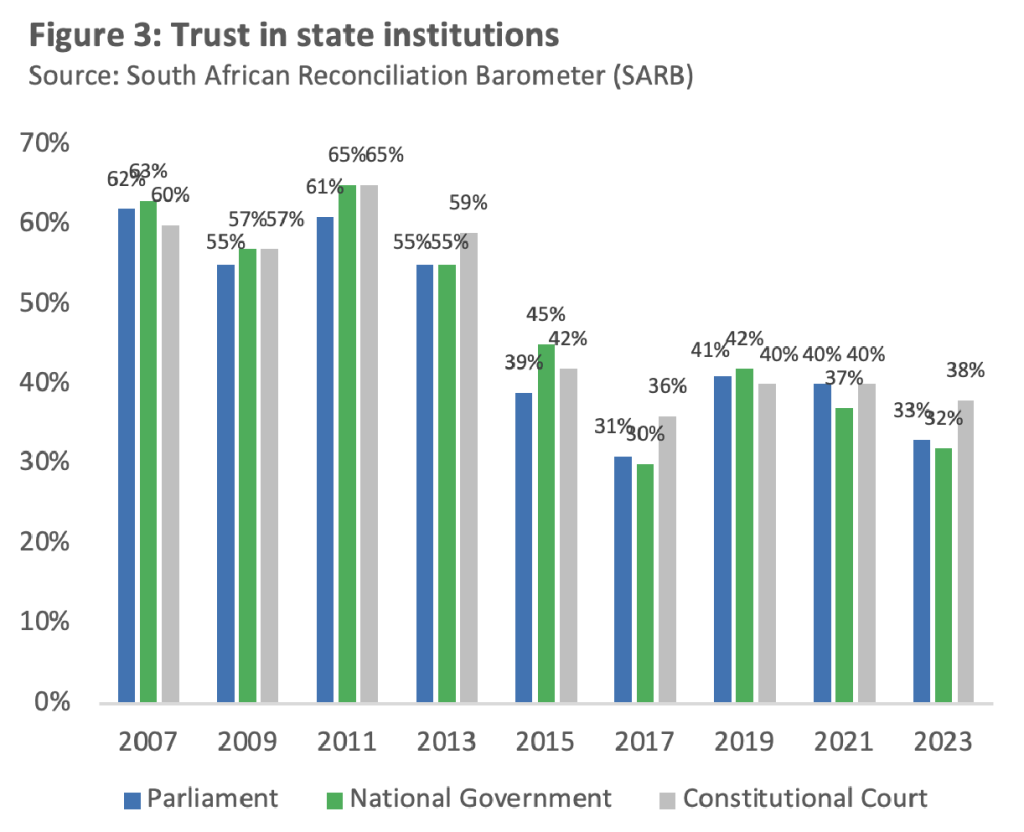

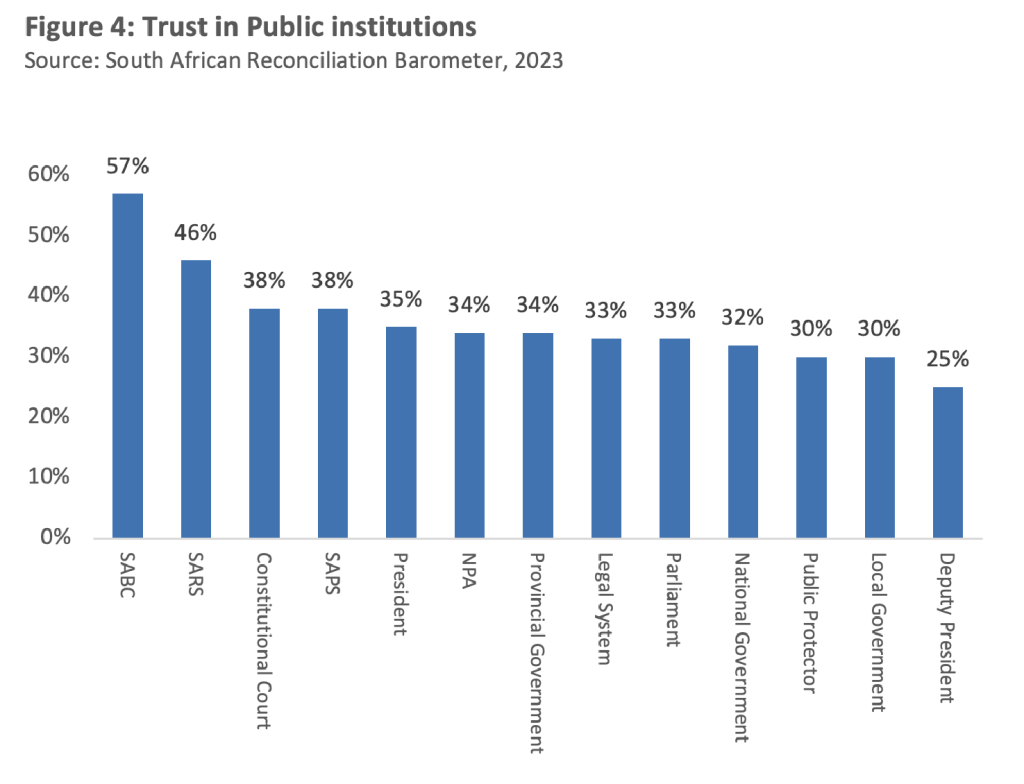

The Afrobarometer findings on citizen perceptions on the dysfunctionality of the country’s democratic system contains within it an indictment of the way in which the constituent institutions of the democratic system seem to function. The South African Reconciliation Barometer (SARB) of the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) – a public opinion survey measuring South Africans’ attitudes towards reconciliation and broader social cohesion processes in South Africa – postulates that the vertical trust that citizens have towards the institutions of state, are equally as important for social cohesion as the levels of trust that exist between different people across different cleavages in society. Launched in 2003, the SARB is the longest running survey of its kind in the world. The insights that it reveals about trust in public institutions are as insightful as they are worrying. In Figure 3 below, trust that South Africans have in the National Parliament (legislative arm), the National Government (executive arm), and the Constitutional Court (at the apex of the judicial arm), are shown. Between the period of the SARB’s first measurements in 2007 and its latest measurement in 2023 – confidence in all three institutions of state have declined by close to 30% for both Parliament and the National Government respectively, and reduced by just over 20% for the Constitutional Court (Lefko-Everett, 2023). Amongst the 13 institutions measured in the 2023 round of the SARB (see Figure 4), only one institution, the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) as a public media outlet, managed to attract a trust level above 50% at 57%.

Question: Tell us how much you trust the following institutions to execute their mandate

Question: Tell us how much you trust the following institutions to execute their mandate

Cumulatively, these findings do not reflect well on the substantive dimensions of democracy. They appear to be failing to resolve, even if incrementally, the country’s most intractable challenges – poverty, inequality, and unemployment – but also appear incapable of addressing many of the systemic challenges that flow from them. In terms of the public opinion data at our disposal, South Africans are unhappy with the direction that their country is moving in and the failure of its democratic system to arrest its perceived decline. As a result, the legislative, executive and judicial arms of the state and the institutions that constitute them are increasingly struggling to retain the trust and confidence of South Africans.

As is the case in all democratic societies, South Africans have a recourse to judge the performance of those that they mandated to be custodians of power in government through regular credible elections. The vote in democratic societies provide citizens with an opportunity to vote for the kind of government they would like, and to reward those who have performed well in government and punish those who did not. In the May 2024 South Africans were able to exercise this democratic right for the seventh time since the 1990 -1994 transition to democracy.

In the light of the African National Congress (ANC’s) faltering track record in prudent and proper governance since the late 2000s, many expected that the hitherto governing ANC would struggle in the 2024 elections to retain an outright majority, and to be able to form a government on its own. The final election result surprised everyone, including the ANC. The ANC’s support plummeted by 17 percentage points from 57% to 40%, while support for the official opposition, the Democratic Alliance (DA) increased by 1% from 21% to 22%, and support for the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) decreased by 1% from 11% to 10%. The other major surprise was the relatively strong performance of the newly formed Umkhonto we Sizwe Party (MKP) of former President (of the ANC and of the country) Jacob Zuma, which in its first election, became the party with the third largest presence in parliament. They garnered 15% of the vote.

Consequent to this result, the ANC faced the difficult choice of either going into opposition, governing as a minority government, or inviting other parties into a governing coalition to co-govern with it. It has opted for the latter, although choosing to refer to it as a government of national unity (GNU), which harks back to the inclusive government arrangement of the first post-apartheid administration that granted all parties above a threshold of 10 percent support, a place in the executive order to create a sense of collective ownership of the processes of governance in an emergent democratic South Africa.

Do South Africans really want coalition government at present?

It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that the outcome of the coalition negotiations will be instructive for the country’s developmental trajectory. At a global historical juncture referred to as a “poly-crisis”[1], or “perma-crisis”[2] – much will depend on the seventh democratic administration’s capacity to rehabilitate public institutions, orient them towards a developmental mandate, and reset the domestic economy on a path towards greater equity while, enhancing the country’s longer-term global competitiveness.

It will have to do so in conditions not of its own making, and in a configuration that has been foisted upon it consequent to the election results. Though a coalition government was not the preferred outcome, particularly for the ANC, in the wake of the election results – both the ANC and DA separately claimed that the election outcome signified voters’ preference for their respective parties to enter a coalition type arrangement.

But is this really the case? Did voters mandate political parties to form a coalition government, or is this merely a matter of contingency arising out of the fact that no party achieved a majority?

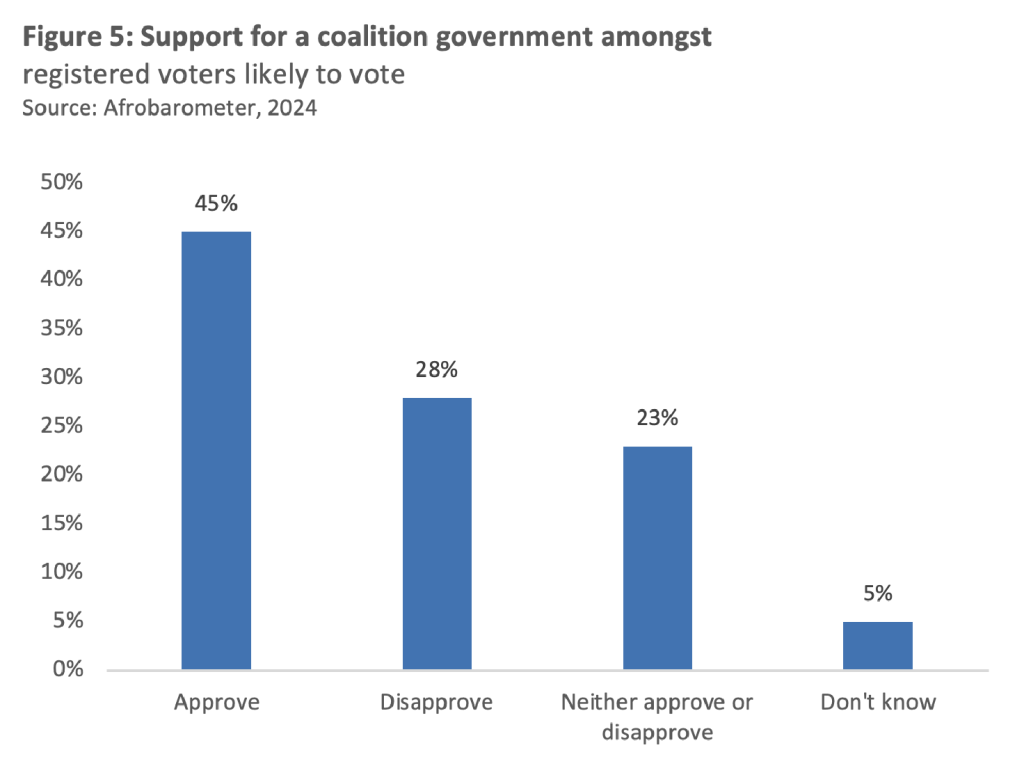

Between the 23rd of April and 11th of May 2024, the Institute for Justice of Reconciliation, on behalf of Afrobarometer, conducted a telephonic pre-election survey amongst a representative sample of 1,800 South Africans to measure their sentiment towards the upcoming elections. Given the possibility of the ANC losing its outright majority, the survey probed South Africans’ receptiveness towards the idea of a coalition government. The question “Do you approve or disapprove of the idea of a coalition government?” was asked to respondents who had indicated that they have registered to vote AND that they were likely to turn out to vote. Responses to this question amongst registered voters indicating a likelihood of voting in Figure 5 suggests that respondents do not seem to provide an emphatic corroboration of the ANC, DA, and an increasing number of other parties’ interpretation of the poll outcome. Figure 4 shows that less than half of respondents (46%) signalled support for the idea of a coalition government, while close to a third (30%) indicated their disapproval for a government consisting of several parties. A further 20% noted their ambivalence about the formation of a governing coalition.

Question: Do you approve or disapprove of the idea of a coalition government, in which two or more political parties run the country together?

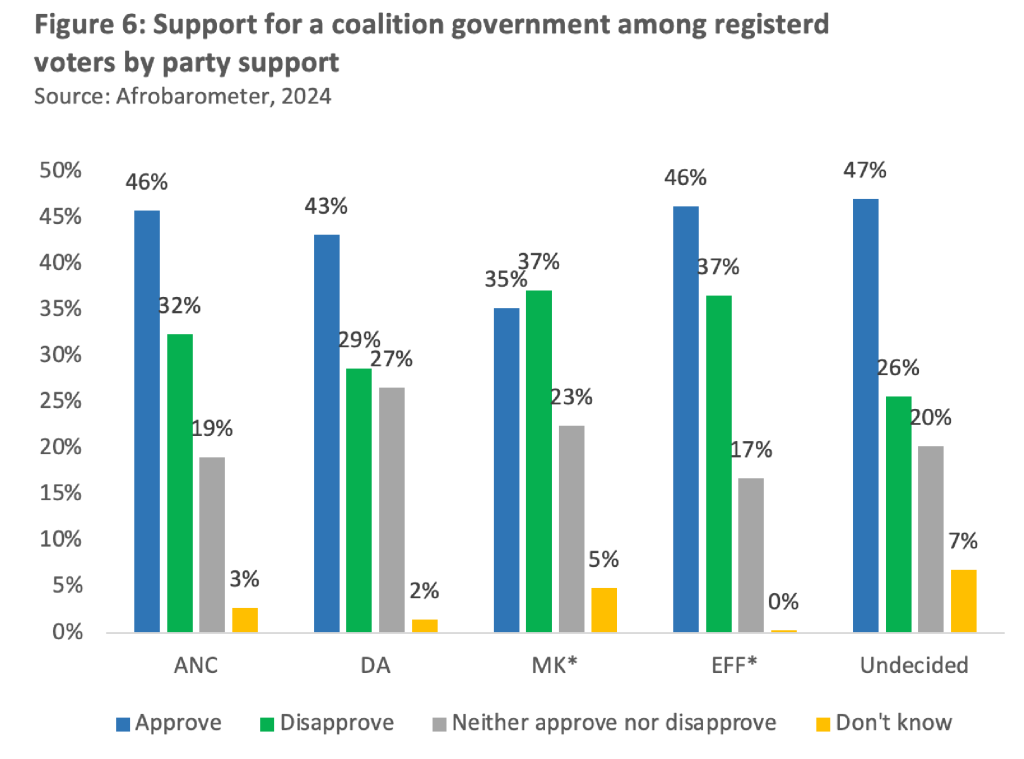

When responses to the same question is broken down by party support (or affinity to a party) among respondents who indicated that they have registered to vote and who were likely to vote (Figure 6), a similar inconclusive picture emerges. While majorities in each of the parties supported the idea of a coalition government, none of them amounted to an outright majority of more than 50%. Interestingly, the highest level of support for coalition government came from “undecided voters” (47%), while the lowest support (35%) came from MKP supporters.

Question: Do you approve or disapprove of the idea of a coalition government, in which two or more political parties run the country together?

Overall, there did not appear to be strong support for the idea of a coalition government amongst registered voters who had indicated an intention to vote. However, those who rejected the idea, remained ambivalent about it, or otherwise did not express a view (the: “don’t know” response) far outnumbered those who were in support of it. These findings show that there may be some ambivalence among voters about the political parties’ contention that the election outcome signalled a preference for coalition government.

Bibliography:

Lefko-Everett, K., 2023. South African Reconciliation Barometer Survey: 2023 Report, Cape Town: Institute for Justice and Reconciliation

[1] multiple different but interlocking problems facing societies, all with major adverse impacts occurring simultaneously and compounding each other’s effects, because of inappropriate policies which are seemingly difficult to tackle and resolve individually. It refers to a convergence of crises that pose significant challenges to governance, stability and societal well-being and include factors such economic crises and downturns, political instability, social unrest, environmental disasters, and health emergencies.

[2] A period of instability and insecurity, the result of either natural disaster, or poorly configured policy whose ill -effects become entrenched, and seem unresolvable. It is suggestive of a situation where crisis conditions persist to become systemic, where societal, political, economic, environmental and other problems become chronic and entrenched, making it seem impossible to find sustainable solutions.