Women’s voice, media power & patriarchy – a toxic mix perpetuated in run up to elections

Justifiably, in the lead up to electoral processes, media coverage tends to focus on providing coverage to political parties and the issues at stake in the elections and in society – fairly, accurately, comprehensively, and equitably. While useful, focusing only on these issues, ignores the lived reality of people in society, and tends to ignore the core questions of dignity and equality.

Women make up 51% of the population of South Africa, and more women tend to vote than men. According to the IEC, there were more women registered voters, than men, but on examining media coverage, a radically different picture emerges.

Globally, women’s voices are under-represented, constituting between 23% and 25% of news coverage.

It’s easy to blame media for perpetuating inequality and not offering us a picture that assimilates demographics, but that would ignore the role media plays in a society.

Two key elements of the role of the media are essential when considering women’s voices. The first is informed by cultural studies and asserts that the news media, rather than being an objective mirror of our society, re-presents the society in terms of existing power dynamics within the society. Even though there are more women in our society, the lived reality is that we live in a patriarchal society dominated by powerful men, powerful male oriented ideologies, social relations, and practices. Women tend to have less power in our society than men, whether it be in government, political parties, business, media or in the domestic sphere. Add in intersectionality, and not only do power dynamics become more complicated, but it also reveals that women experience discrimination based on race and class, in addition to other layers and forms of discrimination. The consequence is that media portrays existing power dynamics, and so the views and voices of men dominate. This does not mean that there are no powerful women, or that the power of women has not increased somewhat, or that there has not been a shift of power in society. Because power in society still lies largely and predominantly in the hands of men, the media will be dominated by their voices.

Voice matters, because those who speak and covered in the media are perceived to have power or hold important positions and worthy and important views. Consequently, some will argue that media are merely representing existing power dynamics as they exist in society, and flowing from the general inequalities, particularly unequal gender relations, is the reason why there are so few women represented in the media. These broader societal issues are to blame for the vastly inequitable treatment of women’s voices in the media.

A second key element of the role of news media in our society is summed up by the unattributed expression, “news media don’t tell us what to think, but they do tell us what to think about.” In other words, the news media, don’t simply re-present power dynamics in society they also help frame how the news is told and what issues and stories get to make the news. Often these two elements work to reinforce each other. Gender based violence is near epidemic levels in South Africa yet less than 0,2% of elections stories were about gender-based violence – either what parties proposed to do to prevent it, or even just politicians talking about the issue on the campaign trail. In this way a central issue of significance for societies stability, people’s security and sustainability is marginalised. It is an uncomfortable truth that parties appear to prefer to steer away from, and the news media – for the most part – tend to avoid, leaving a major issue for women’s safety and security and social stability, ignored.

While the two explanatory elements attempting to explain the role of news media – as a mirror of society and as shaper of opinions and attitudes – help us understand, to a degree, why women’s voices and critical issues are marginalised, they do not help us highlight the reality that the news media itself, has agency, they are critical duty bearers in a democracy and have an important role to help frame and set the news agenda. While there is little doubt that societal norms and general journalistic practice will mean many media professionals will commonly re-present male power, it doesn’t mean that journalists can’t do things differently. Our media in South Africa – while facing extreme threats to sustainability nonetheless have high levels of media freedom. There is nothing for example preventing a newsroom from saying they will only access women in the news. They could for example have newsreaders reading what men in power have said instead of direct audio clips. Similarly, there is nothing to stop any newsroom from saying they will have a minimum number of pieces or stories about women, or from ensuring that their journalists would have a clear gender framed question posed at every news event or conference that they attend. These examples may sound extreme but there is no legal or ethical barrier that would prevent them or any multiplicity of alternatives from being implemented. Of course, structural change is easier challenged in theory than practice. There are also ongoing efforts by media structures like the South African National Editors Forum (SANEF), the Press Council, and key editors to address gender inequality in the news.

In the run up to elections MMA monitored over 75 news media. For the most part media fell in line with the average as indicated in the chart below. We wanted to highlight the top five media who had female sources above the average number of sources. We looked at all our media monitored where they had more than 24000 known sources. This might seem low but smaller media who produced fewer pieces should also be recognised for their efforts. Accordingly the media outlets listed below should be commended for having more female voices and seeking attempting to address gender biases and gender inequalities in news coverage generally and in amplifying women’s voices (even if insufficiently).

| Daily Dispatch | Male | 75% |

| Female | 25% | |

| Daily Sun | Male | 74% |

| Female | 26% | |

| Grocotts Mail | Male | 78% |

| Female | 22% | |

| GroundUp | Male | 60% |

| Female | 40% | |

| Sowetan | Male | 77% |

| Female | 23% |

Interestingly two of the top five are smaller media entities, and the news entity with the highest level of female sources was GroundUp. It is disappointing that no broadcast media are in the top five, and especially noteworthy, is the absence of any public service media featuring in this list.

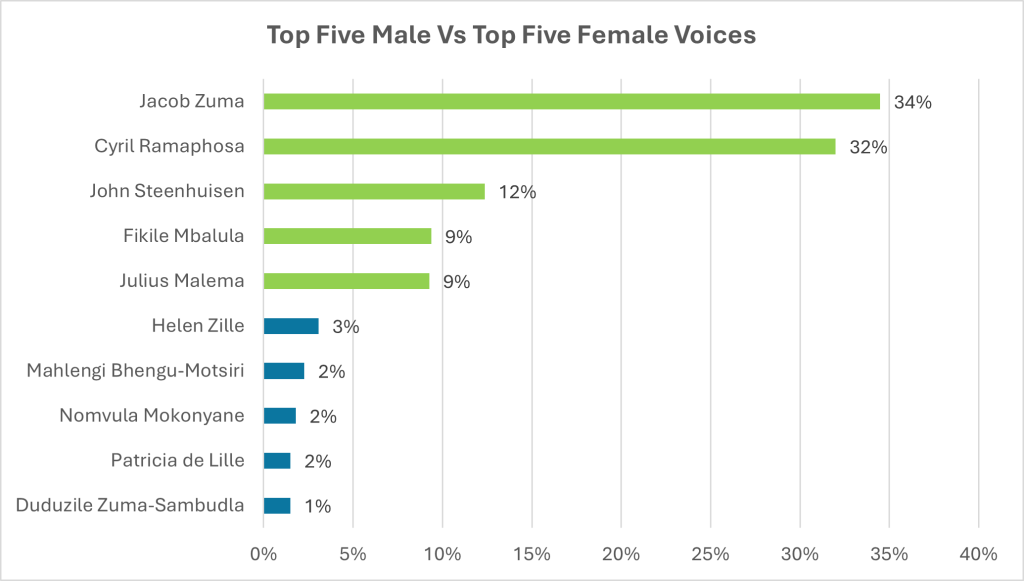

GroundUp’s performance on addressing the gender imbalances in news and expert sources is significantly above average, but it is worth noting that GroundUp does not cover general news, like Daily Dispatch, Sowetan or other traditional news media. This matters precisely because in elections coverage parties, tended to put forward more male voices and this may skew the statistics somewhat. Notwithstanding this, GroundUp’s results do however demonstrate that a concerted effort to access more women can shift overall output. Despite the efforts within newsrooms, the overall levels are hugely disappointing. Journalists we engage with, in private, community and public media are strongly critical of the low levels of women’s voices. They highlight that much of the blame needs to be laid at the doors of political parties. Certainly, the overwhelming majority had very few if any women in senior leadership positions. The graph below shows a comparative visual of the top five male sourced voices, versus the top five female sourced voices during the election period, from political parties. The data shows us that the top sourced female voice, Helen Zille, held just 3% of the voice share, versus Jacob Zuma, the top sourced male voice, who received 34% of voice share. The contrast is extraordinary.

News media also comment how, despite efforts and positive initiatives to provide and access more women, because of the lived power dynamics, men tend to be more easily accessible. Men tend also to be available at all hours, while women tend still to be the main carers meaning they tend to have less availability after hours. Also, journalists in broadcast note that men find it easier to travel to and from interviews and are more commonly open to being accessed. The reality of sexual harassment and general safety also means that while some women may be more open to being accessed, they are understandably more reluctant to receive and engage with unsolicited calls and requests.

As MMA’s broader media monitoring highlights, South African media performed well in relation to overall fairness of coverage. See: “Was the Media a Mirror, a Megaphone, or just misplaced in its Coverage of the 2024 South African Elections?”

It is essential however to consider that fair coverage during the electoral period needs to be not only balanced, fair and accurate but also inclusive. Inclusive coverage aids free and fair electoral processes. More women’s voices make sense not just because more women vote, but because it helps with greater diversity of views and opinions. Fundamental gender inequality perpetuated by political parties and news media, maintains the status quo, undermines public trust – why would women want to trust media and parties that only give men a voice? – and further undermines free, fair and credible elections.